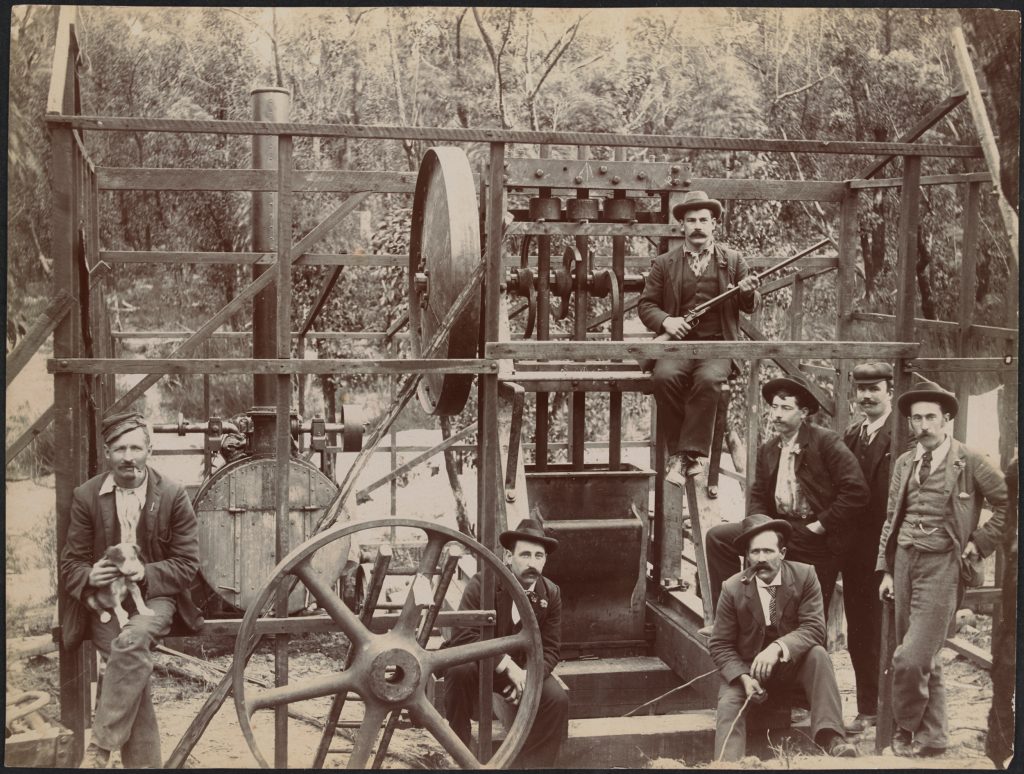

The Goldfields

The history of the Central Victorian Goldfields is an assembly of a great range of events, stories and layered change. These stories have been told many times and in many different ways.

The natural landscape formed some 500 million years ago. Through a series of dramatic changes caused by tectonic forces, erosion, volcanic activity, climatic change and water flows, the region’s alluvial and deep lead gold deposits were formed.

Aboriginal peoples have lived in the area for at least 50,000 years and witnessed many significant landscape changes. The area is part of the Kulin Nation, a federation of five distinct but closely related communities. The Kulin Nation covers 2 million hectares of what is now referred to as south central Victoria. All Kulin communities share the same moieties (totem): bunjil, the wedge tail eagle, and waa, the crow. Individual moieties are patrilineal and determine behavior, social relationships and marriage. For thousands of years the Kulin nations maintained a network of alliances that influenced meetings, ceremonies and complex trading networks that extended beyond what is now the state of Victoria.

Aboriginal peoples continue to remain strongly connected to these landscapes today and seven Registered Aboriginal Parties are the primary guardians, keepers and knowledge holders of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage – Barengi Gadjin (the Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jadawadjali, Wergaia and Jupagulk peoples), Dja Dja Wurrung, Eastern Maar, Taungurung, Wadawurrung, Wurundjeri and Yorta Yorta peoples. Their ancestors shaped the landscape through their activities, knowing it deeply and imbuing it with important cultural and spiritual meanings. The whole Country embodies songlines and storylines that connect Aboriginal peoples to places. Through their cultural practices, stories and traditions, knowledge was built and shared, generation by generation and continues to be today.

Displacement and loss is also part of the story for Aboriginal peoples. By the time the gold rushes commenced, Aboriginal populations had been severely diminished and various policies had been implemented with respect to their presence on the land. At the very least the fences and strange animals of pastoralists were a source of confusion and difficulty for these communities. Driving Indigenous peoples from the land, depletion of native animals and plants, and abandonment of Aboriginal land management practices was even more significant. There are records of bloody clashes between white settlers and tribal groups.

The gold rushes did provide some opportunities for Aboriginal people. Some were able to find employment with pastoralists, whose white labourers had disappeared to the goldfields. There is some evidence of trading with miners and a Native Police Corps was established, which did not necessarily provide a basis for a strong positive relationship with the miners.

The rush to get rich commenced in earnest after discoveries of gold at Clunes and Buninyong in July and August 1851. By 1852 the rush to Forest Creek (Castlemaine) and Sandhurst (Bendigo) was underway and within a decade the colony’s population had grown from 77,345 to 540,322. This established Victoria’s multicultural population as miners arrived from all over the world. This aspect of the regions character is most easily recognised in the names of many of the towns and villages, but can also be uncovered in the headstones of the many cemeteries in the region, in the names listed on war memorials and avenues of honour and the myriad of different churches and places of worship and the denominations which are closely associated with different ethnic communities, while Aboriginal names were also adopted, such as Ballarat, Kyabram, Moorabool, Tongala, Waubra, and many others.