Aboriginal Peoples have lived in the part of Australia known as Victoria for at least 40 000 years. The Aboriginal clans who occupied the region of what is now the municipality of Bendigo at the time of European invasion were the Dja Dja Wurrung people and the Taungurung people.

Both the Dja Dja Wurrung Clans and the Taungurung Clans are part of the Kulin Nation, a federation of five distinct but closely related communities. The Kulin Nation covers 2 million hectares of what is now referred to as south-central Victoria. All Kulin communities share the same moieties (totem): bunjil, the wedge tail eagle, and waa, the crow. Individual moieties are patrilineal and determine behavior, social relationships and marriage. For thousands of years the Kulin nations maintained a network of alliances that influenced meetings, ceremonies and complex trading networks that extended beyond what is now the state of Victoria.

The people through bloodline and kinship known as the Dja Dja Wurrung Clans are also known as the “Jaara”. The Jaara identify as the “Dja Dja Wurrung”, meaning “Yes Yes tongue/speak” which relates to the collective language group. The Dja Dja Wurrung is recognised as having 16 or more clans with similar dialects. In addition to the City of Greater Bendigo the following Local Government areas are situated on Dja Dja Wurrung Country: Loddon, Buloke, Northern Grampians, Central Goldfields, Pyrenees, Ballarat, Hepburn, Mount Alexander, Macedon Ranges and Campaspe.

Taungurung Country extends from the Dividing Range to the rivers east of the Campaspe River as they enter the plains to the north. In addition to the City of Greater Bendigo the following Local Government areas are situated on Taungurung Country: Campaspe, Strathbogie, Mansfield, Murrrindindi, Greater Shepparton, Mitchell, Macedon Ranges and Mount Alexander. There are nine clans of the Taungurung. The clan that inhabited the area of Heathcote, part of the Greater Bendigo municipality, were the Nira-Balluk.

The history of Greater Bendigo’s Aboriginal peoples is ultimately one of resilience. While European settlers destroyed food and water sources and many cultural sites and places, including the introduction of exotic flora and fauna and the introduction of foreign diseases, they have remained resilient and maintain a strong culture including connection to their country in the Greater Bendigo municipality. Today the Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation and the Taungurung Clans Aboriginal Corporation are the Registered Aboriginal Parties and are the voice of Traditional Owners in the management and protection of cultural heritage. Greater Bendigo today is also home for Traditional Owners and Aboriginal people from different nations from across Australia and Torres Strait Islands.

The first discoveries of gold at Bendigo were in 1851 in conjunction with the rushes further south at Mt Alexander. The real rush to Bendigo (Sandhurst) took off in early 1852 with discoveries at Golden Point along the Bendigo Creek and then soon after at New Chum, Long Gully, Eaglehawk Gully and Red Hill. The list of localities around Bendigo where gold was discovered in 1852 is extensive. By the middle of 1852 it was reported that more than 4000 or 5000 diggers were arriving each week.

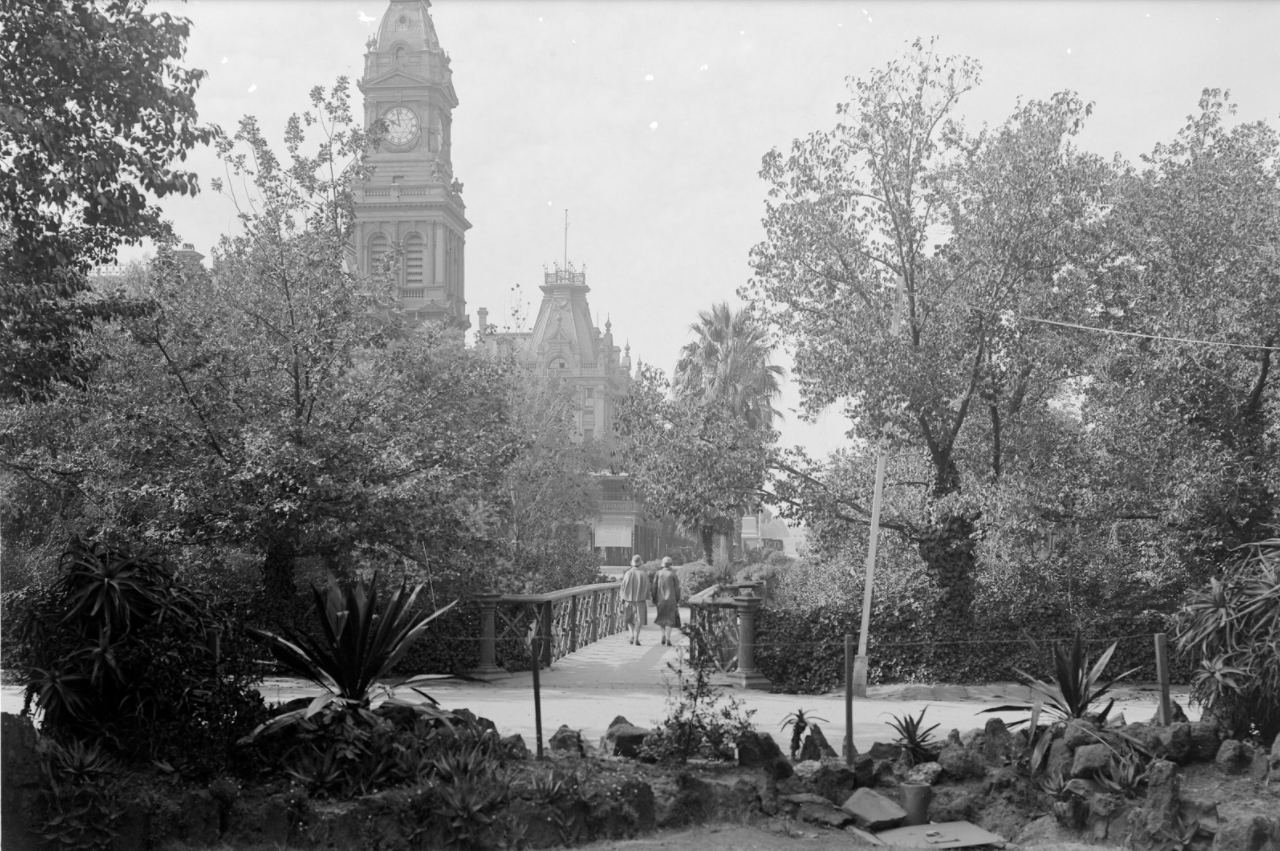

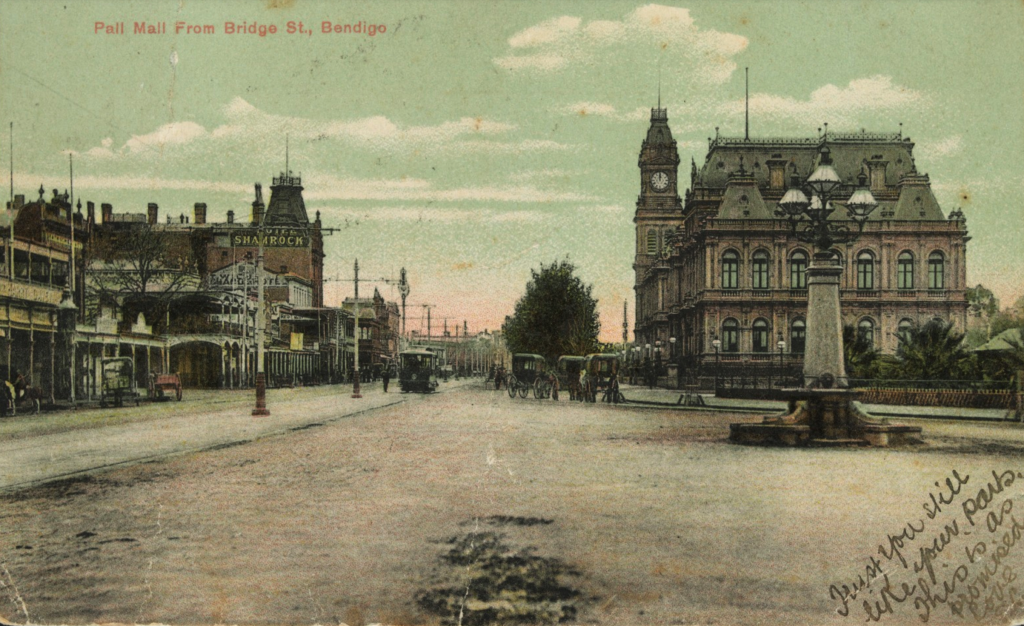

Bendigo, first of all grew as a series of separate mining encampments, clustered around the gold discoveries. These small settlements gradually acquired pubs, stores and houses, initially of rough wood or canvas, but later taking on a more permanent form. The most significant of these settlements was that around the Bendigo Creek, the current centre of the municipality. The first survey of this part of the town took place in 1854, with the ambitious William Larritt setting out the formal Pall Mall, the bowed Lyttleton Terrace to the east and a major garden reserve to the west. This all alluded to city models from Britain.

The rough edges of the diggings were vanishing by the early 1860s, but Sandhurst took some time to acquire the trappings of a grand commercial centre. The grandiose name of Pall Mall did not live up to itself for some time. Well into the 1860s it was a muddy thoroughfare and McCrae Street was impassable after heavy rain. Equally the greater city that we know took some time to take shape. The transformation from a series of diggings to a town really only commenced once the rushes had abated and small hamlets of a more permanent nature took form. In some cases this really didn’t take place until the 1880s.

One of the great problems for the diggings both around Bendigo and further south into the current Mt Alexander Shire was the shortage of water. The development of the Coliban Scheme with its storage reservoirs at Malmsbury and Barker’s Creek and ultimately 388 miles of channel and 315 miles of pipes distributed water across the diggings and by 1877 was delivering water from Malmsbury to Bendigo. Much of this network operates to this day.