Campaspe Shire’s history goes back thousands of years to the days of the traditional owners, while European settlement in the shire started the first half of the 19th century.

The Campaspe region has a strong and rich Aboriginal culture, going back at least 26,000 years and evident in the range of significant Aboriginal sites including Murray River, Kow Swamp, Lake Cooper and Kanyapella depression. Traditional Owners have unique rights to their country. Aboriginal People are the primary guardians, keepers and knowledge holders of Aboriginal cultural heritage.

Campaspe Shire incorporates three Traditional Owner Groups: Dja Dja Wurrung, Taungurung; and Yorta Yorta.

The first European sighting of the southern portions of the current Campaspe Shire came in 1836 when Major Thomas Mitchell returned from his overland journey from Sydney to Portland. He was soon followed by Joseph Hawdon and Charles Bonney, who brought cattle overland from NSW in 1838. By 1840 pastoralists had taken up runs throughout the area and it was these runs that formed the basis of the local economy to the present day.

At the same time the colonial government was in the process of setting up Aboriginal Protectorates and in 1839 the Protectorate at the “Old Crossing Place” (where Mitchell had crossed the Goulburn was established. By 1840 it had been moved to the current site of Murchison under the management of William Le Souef. By 1850 the protectorate system was largely abandoned and the Murchison Protectorate was closed. The last Protector, Dr James Horsburgh established a medical practice and the Aboriginals were left to fend for themselves. The discovery of gold in the region would have created an even more foreign environment for them.

The first discovery of gold in this southern portion of the Shire was made by diggers from Bendigo moving overland to a new field at Beechworth. This was in 1853 near modern Rushworth. The finds at nearby Whroo occurred soon after and for the rest of the nineteenth century the Whroo field was known as the “Wet Diggings” and the Rushworth field as the “Dry Diggings”.

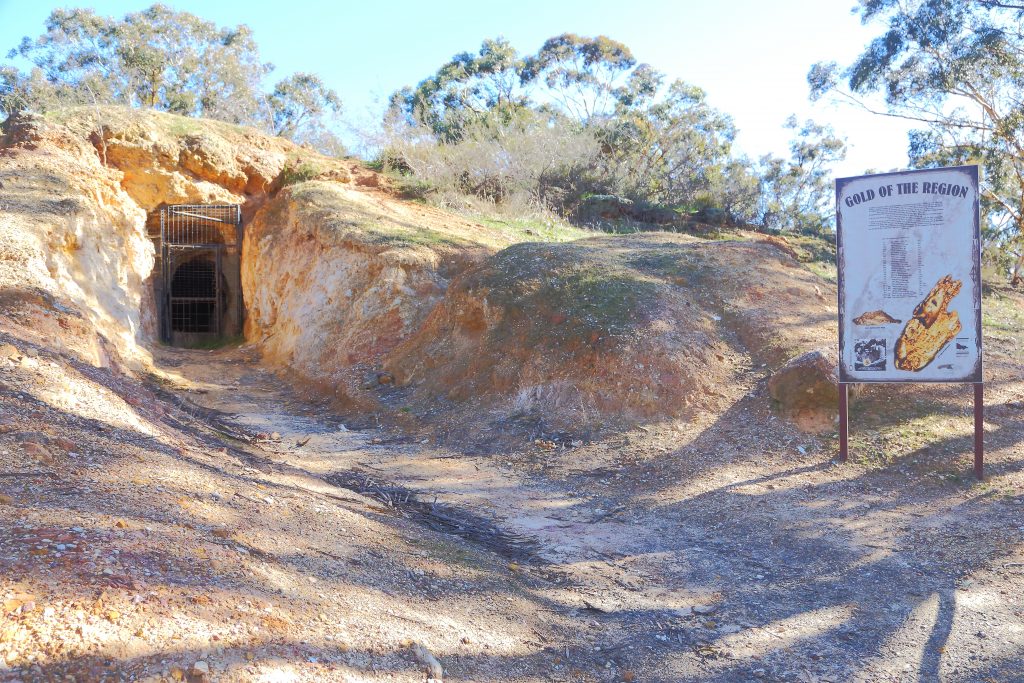

As with all the fields the initial activity was on the surface, digging shallow shafts and using puddling machines. Men with access to capital sunk deeper shafts gaining access to the quartz reefs. The most dramatic of all the mines in this part of the State was that at Balaclava Hill near Whroo. Initially a series of tunnels and shafts it was eventually worked as an open cut. It was named after one of the fiercest battles of the Crimean War, because it had been discovered on the same day as that battle.

The fields around Rushworth and Whroo were small compared to other parts of the central goldfields, but they were often referred to as the richest in terms of the high average yield of gold produced.

The miners in these fields were perennially plagued by problems with water, either through shafts flooding or creeks drying up leaving miners without water to drink or wash gold. At one stage diggers at Rushworth were carting their wash dirt six miles to a lagoon to wash it. There are also reports of water being carted 12 miles to Whroo from the Goulburn River.

The numbers of diggers rose and fell throughout the 1850s. They were a fickle lot and a new discovery would see them move on, only to return should another reef be uncovered. In 1856, 5,000 diggers were working at the Old Lead. Amongst these diggers were several thousand Chinese, who as with elsewhere stayed on long after the European miners had moved on.

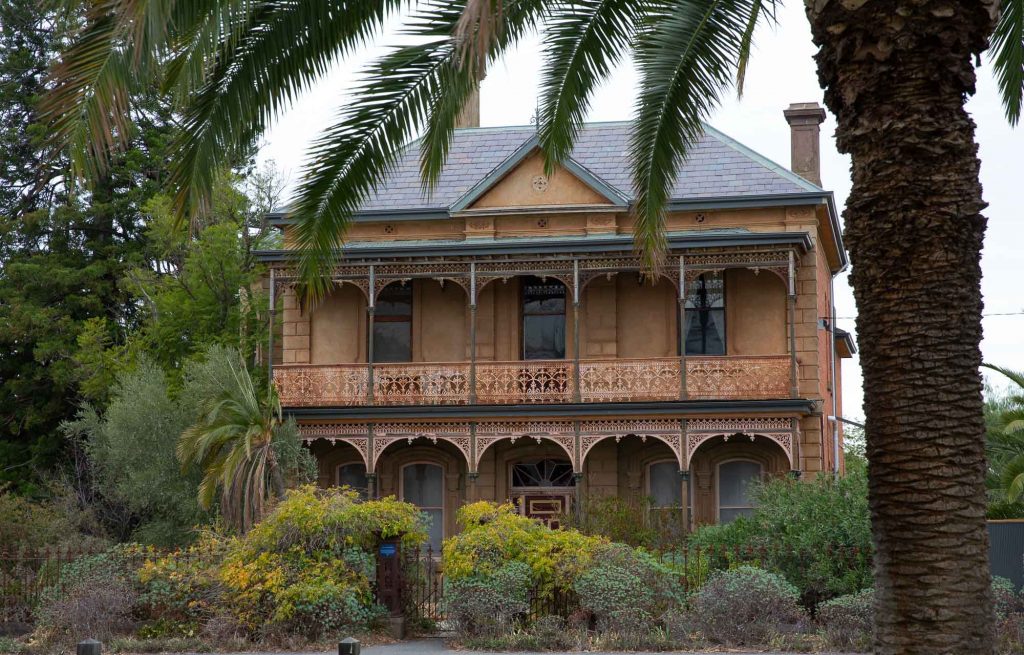

Heritage in Rushworth

By 1859 there were still enough Chinese on the Rushworth and Whroo fields for there to be bitter attacks against them by Europeans, including pursuing them through the law. By 1860 at least 100 Chinese had been prosecuted for not having residence licences and there are records of fights at Whroo between Chinese and Irish miners.

By the 1860s the easily discovered gold was gone and it was left to newly established mining companies to dig deeper and rely on more sophisticated technology than picks and shovels, such as crushing machines to extract the gold. The departure of the alluvial miners left a denuded landscape and the remnants of settlements.

The Balaclava Hill Company was one of the more successful in these fields, during the 1860s buying up adjoining claims and expanding its operations. This mine continued for many years and proved to be highly lucrative. Between 1866 and 1881 it produced 85,000 tons of quartz and from that extracted 85,000 pounds worth of gold. By the late 1880s its activity had all but finished and all it left behind was the enormous open cut crater at Whroo.